by AGS Member Karen Jones

In 1859, the issue of slavery was on every American’s mind. Most of the white people in the agricultural South could not imagine life or Southern culture without enslaved Black people. Meanwhile, in the North, the idea was repugnant to a growing number of anti-slavery activists. And it was intolerable for those held in bondage. The inevitable clash was on the horizon.

One of the most surprising stories discovered while writing about ancestors is that of Columbus Jones.

Columbus was born in 1840 to enslaved parents owned by ancestors Ambrose and Shada Ann Jones, living in Macon, Georgia. At the time, Ambrose Jones was being forced to sell property and slaves to pay taxes and his debtors due to the existing economic downturn.

By the time Ambrose Jones moved to Pensacola, Florida, later in the 1840s, he had no land left, and was making his living by hiring out those he enslaved to others. The 1850 census recorded that Ambrose Jones owned fourteen enslaved persons, including Columbus and his mother. They lived in a village of workers who were building the federal Navy Yard in Pensacola. When Ambrose Jones died in 1853 without a will, his estate became the property of his widow Shada Jones, who continued to hire out the slaves, including Columbus, just as he was becoming a teenager.

But Columbus resisted and was punished for it. He made several unsuccessful attempts to escape and was caught each time, after his owner Shada Jones posted notices for his return. The Fugitive Slave Acts, enacted by Congress to pacify the Southern states, made it illegal to help an enslaved person escape. Despite that, anti-slavery people defied the law and developed the “underground railway” to help runaways reach freedom in Canada. But Pensacola was very far from Canada.

In 1859, Columbus Jones was hired out to the Pensacola Navy Yard when he decided to make another run for freedom, this time by sea. Details of his escape attempt come from newspapers of the day. Stowing away on a ship bound for Massachusetts, Columbus was given food by sympathetic crew members for several days before being discovered by the captain. Bad weather prevented putting in at a port where Columbus could be turned over to a federal marshal and returned to Shada Jones. Restraining the strong and resolute man was difficult, for he broke three sets of iron shackles before being confined in the “caboose.” Columbus told the crew that he would never go back to slavery alive.

The brig continued its journey to Massachusetts. Arriving at the ship’s home port of Hyannis, the acting captain anchored out in the bay and went ashore in a smaller boat to seek advice from the regular captain and the shipowner about what to do with Columbus Jones.

A New York newspaper account tells the story:

“While [the acting captain] was gone, Jones managed to effect his escape from the caboose, and hailing a skiff from another vessel, offered the man a dollar if he would row him ashore. The man accepted the proposal, and the fugitive got into the boat. The crew on board seem to have been aware of what was going on, but pretended not to observe it, as their sympathies were with the runaway. The skiff put off from the ship and was nearing the shore at Hyannis when it was met by the boat containing [the captain and acting captain], who stopped it, and took Jones [back] to the ship.”

The captain then hired a schooner to take Columbus Jones in chains to the marshal at Norfolk, Virginia, to be returned to Shada Jones.

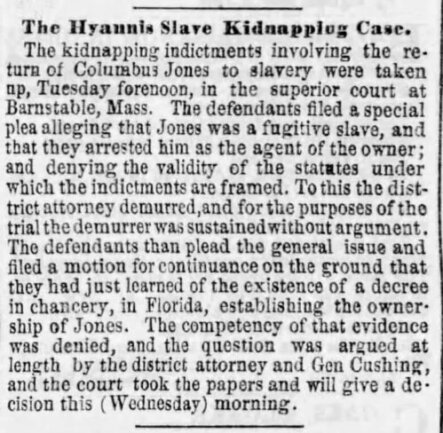

That was just the beginning of what became the sensational “Hyannis Kidnapping Case.” Anti-slavery people onshore at Hyannis had figured out what was going on and reported the case of the recaptured slave to the police. When the ship docked at the wharf without Columbus Jones, the police arrested the captain and mate, charging them with breaking the Massachusetts kidnapping and conspiracy laws. The ship owner and the other captain were also charged.

Several months later, they were indicted and brought to trial. A son of Ambrose and Shada Jones was subpoenaed to come from Florida to testify to the family ownership of Columbus Jones. The trial lasted several days, with arguments about two points of jurisdiction—whether the recapture and transfer of Columbus actually occurred within the county, and whether the Massachusetts law against kidnapping was preempted by the federal Fugitive Slave Acts that required people to return runaway slaves. If Columbus was property, then he could not be kidnapped. That issue was so big that the judge did not want to deal with it. It was easier for the jury to decide that the “kidnapping” had occurred outside the jurisdiction of the county. The defendants were acquitted.

Word of the trial spread far and wide. It was reported in dozens of newspapers throughout the country, both pro-slavery and anti-slavery. In the newspapers of Charleston, New Orleans, Richmond, Alexandria, Nashville, Louisville, and others in the South, the news was greeted with relief that the fugitive was sent back. In the cities of the North, a great uproar occurred, and the name of Columbus Jones became a rallying cry for the cause of abolition.

The American Anti-Slavery Society wrote of Columbus Jones:

“Of the unsuccessful attempts to escape, none became more notorious, or excited more attention, by reason of the issues coming to be involved in it, than that of Columbus Jones, who left Pensacola on the 1st of May, 1859, on board a brig bound for Boston.”

Within two years after the Columbus Jones incident, the divide between North and South broke wide open. After four years of Civil War, the “runaway slave” became a free man.

Image: The Springfield Daily Republican, November 16, 1859, Page 4. via Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-springfield-daily-republican-the-hya/169510202/ : accessed April 3, 2025), clip page for The Hyannis Slave Kidnapping Case

Lineage: Chris Jones1, William Jones2, George Hardwicke Jones3, William A. Jones4, Ambrose Jones (1784 SC -1853 FL) & Shada Wright5 (1796 GA – 1862 FL), Reuben Jones6

Source: “An “underground railway” to Pensacola and the Impending Crisis over Slavery,” Matthew J. Clavin, The Florida Historical Quarterly, Spring 2014, Vol 92, No 4, pp 685-713, www.jstor.org.

Source: “Fugitive Slave Acts,” www.history.com.

Source: “Particulars on the Kidnapping of the Runaway Slave Jones,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Brooklyn, NY, June 1, 1859.those